Cattle feeders aren’t the only ones who have seen price adjustments as production ramps up. Calf prices – including seedstock – have moved in lock step with fed cattle prices, narrowing cow-calf margins as well.

“I think margins will get tighter faster than anyone thought they would,” said Jay Wolf, a member of the third generation at Wagonhammer Ranches, Bartlett, Neb., a family-owned business that’s been in operation more than 100 years. “Everyone manages costs even in good times, but in this environment, some equipment acquisition might be put off for a time.”

University of Nebraska economists have run 2016 budgets for several sizes of operations in several locations, employing data from a survey of producers. Their conclusion confirms Wolf’s observation: Profits have declined compared with 2015 in every budget group.

Lower revenue is a primary cause, as it has dropped 65 percent to 74 percent year-over-year. However, increases in feed costs also contributed to the squeeze in three of four budgets the economists ran. With a cost increase of $251/calf, the budget for 500 cows in the Sandhills showed the greatest bump. This was due to strongly higher grazing lease costs.

Sandhills also saw the largest decrease in profitability – a substantial $916/calf, from a positive $492 last year to an estimated $424 loss this year.

“Lower cattle prices and higher feed costs explain all but $19 of this decline,” according to Roger Wilson, University of Nebraska budget analyst.

In fact, he reports that a 750-cow budget, representative of the Central Agricultural Statistics District in the state, is the only one with a positive profit for 2016 – $218/calf, a $562 decline from last year’s $780.

“Budgets for ranches that rely primarily on owned grazing land may still show substantial profits given the current price structure, if they are not including an opportunity cost for grazing land,” Wilson said. “It may be that the profit is a return on land investment rather than profitability of the cow operation.”

However, Jim Van Kirk, vice president of credit at Farm Credit Services of America (FCSAmerica), observes that an unprecedented number of good years has generally left cow-calf operations in sound financial condition.

“We expect the price impact of bigger calf and beef supplies to continue and even accelerate in the next few years,” he said. “The higher grazing cost is a significant factor that may need to be adjusted going forward.”

Pasture outlook for 2016

With the exception of California and the Southwest, the United States has started the growing season with very favorable pasture and forage conditions. Only 10 percent of total acres were rated poor or very poor, down from 13 percent last year and a five-year average of 21 percent. The Great Plains, at just 8 percent poor/very poor, and the Western region, at 12 percent, have seen the most improvement, while the Southern Plains and Corn Belt are about even with last year.

The Climate Prediction Center’s three-month outlook for May to July promises additional moisture across the southern half of the United States, before the June to August and July to September outlooks shift to neutral -- equal chances of above, normal or below rainfall.

Cow market

As producers adjust to existing and expected lower cow-calf profits, beef cow slaughter is up 4 percent from last year’s levels, while dairy cow slaughter is level, bringing total cow slaughter to about 1 percent over 2015. Bred cows averaged $1,350 to $2,100 in western markets and $1,600 to $2,350 in the Midwest in April; bred heifers, $1,550 to $2,100 in the West and $1,700 to $2,300 in the Midwest; and pairs, $2,000 to $2,500 in the West and $2,100 to $3,000 in the Midwest.

Market cow prices have been quite disappointing, near 91 on CattleFax’s Seasonal Utility Cow Price Index, compared with 104 last year. CattleFax expects cow prices to be flat through spring and summer, in the $70s/cwt. range, dropping to a fall low in the $50 to $60 area.

Hence, the balance is swinging from producers facing a decision between keeping cows to produce another high-priced cow versus selling for a good slaughter price to a decision of keeping for a lower-priced calf for selling for a lower slaughter price.

Wolf expects that in areas such as Nebraska, which remained fully stocked through the liquidation, the decision will be steady as she goes. In areas such as Oklahoma and Texas, where drought forced cattle off the land, additional herd rebuilding is more likely and replacements have gotten more reasonable.

Seeking Efficiency

“In this part of the cycle, it is even more important to know your cost of production at every level of production,” said Jud Jesske, FCSAmerica vice president, agribusiness lending. “It’s a time to make decisions geared to boosting efficiency.”

Main measures that separate high-profit from low-profit operations include calf-crop percentage, weaning rate, calving interval and weaning weight.

An increase in the percentage of cows successfully bred and delivering a calf will have a large impact on profitability. Reducing calf loss will have a similar impact.

The more calves for sale, the more the income and the less expenditure without return on investment. A study from the University of Georgia identified 85 percent as the level required to meet production expenses, on average; 90 percent is considered a well-managed herd. And a goal of a 95 percent calf crop during a 60-day calving season is a target that can be reached, according to Ted G. Dyer, Extension animal scientist at the university.

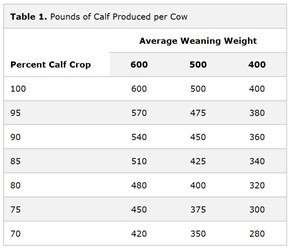

The chart below illustrates the impacts of percent calf crop and average weaning rate. For instance, if a ranch has a weaning rate of 85 percent and weaning weight of 500 lb., over all cows in the herd, that would be equal to 425 lb. per cow. At 90 percent, pounds produced increases to 450 lb.

SOURCE: UNIVERSITY OF GEORGIA

An improved calving interval not only means less cow downtime, but the more calves born on the early end of the calving season, the more pounds there will be at weaning. For instance, a calf born 15 days earlier will weigh about 30 lbs. more if one assumes a 2- lb.-per-day rule of thumb for gain.

One recent survey found a 50 lb. difference in weaning weight between high-return and low-return producers. At last year’s prices, that would have been about $125/calf in added return.

“We expect several years of tighter margins and FCSAmerica is looking at all options to help producers get through this challenging time,” said Jesske. “It may be early to say this, but at times, that means looking beyond cash-flow and considering restructuring loans to provide working capital or even considering different business models.”